Airbnb helped generate $1.2 billion in economic activity in Austin in 2023

Key Takeaways

- Airbnb released a report showing hosts and guests in the Austin metro area contributed an estimated $1.2 billion in economic activity in 2023.

- Hosts in the Austin metro area helped support approximately 14,800 jobs and generate $269 million in total tax revenue.

Key Takeaways

- Airbnb released a report showing hosts and guests in the Austin metro area contributed an estimated $1.2 billion in economic activity in 2023.

- Hosts in the Austin metro area helped support approximately 14,800 jobs and generate $269 million in total tax revenue.

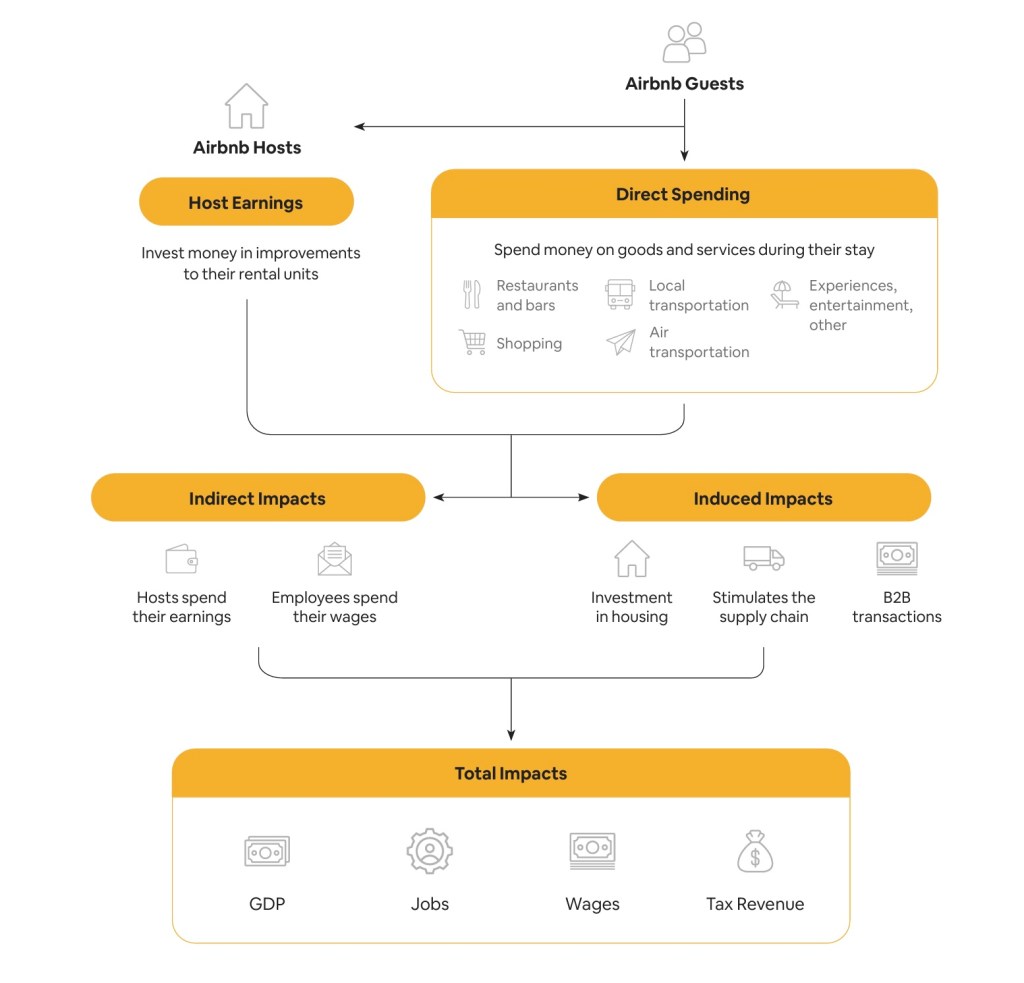

Airbnb released a report showing hosts in the Austin metro area welcomed nearly 1.4 million guest arrivals who contributed an estimated $1.2 billion in local economic activity in 2023.1

The report offers data-driven insights into the benefits home sharing brings to the greater Austin area. By welcoming guests into their homes who then spend money on local businesses, hosts in the Austin metro area helped support approximately 14,800 jobs2 and generate $269 million in total tax revenue.3

Hosting on Airbnb is also a vital source of supplemental income for local residents. According to a 2023 survey of hosts in the Austin metro area, 52 percent said the income earned through hosting has helped them stay in their home, while 15 percent said hosting helped them avoid foreclosure or eviction. For the majority of hosts in Austin, eliminating the revenue earned through Airbnb would be a major financial blow, in some cases undermining their ability to afford to live in the region.

“This new analysis underscores how home sharing is an important economic engine for the Austin area, allowing residents to turn their home into a source of extra income that helps them afford to live in Austin, while ensuring neighborhoods and businesses across the City benefit from tourism,” said Luis Briones, Airbnb Senior Public Policy Manager. “We hope Austin leaders will use these findings to ensure hosts, guests, and the greater Austin community can continue to enjoy the benefits of home sharing.”

The report also analyzes the housing market in the greater Austin area—a region that has seen significant economic changes and a doubling of its urban population size since 1990. Driven in large part by these broader shifts, housing costs began rising higher than income long before Airbnb was even founded. While rents and home prices in Austin have seen some recent declines as more supply has been added over the past year, the most significant long-term driver of rising housing costs in the region is chronic underproduction of new housing over many years.

According to Airbnb’s analysis, 481,000 housing units would have needed to be added in the Austin metro area over the last five years to stabilize rent growth at the rate of inflation, but only 178,000 units were actually constructed over that time.4 By contrast, entire home listings on Airbnb booked for more than 90 nights a year represent just 0.5 percent of the Austin metro area’s 1 million housing units.5

There is also little evidence that regulations aimed at limiting short-term rentals have successfully brought down housing costs. For example, after New York City implemented strict regulations removing thousands of short-term rentals, rents still increased by 3.4 percent during the first 11 months of the law and vacancy rates remained unchanged. The primary beneficiaries of New York City’s regulations have been hotels, which saw prices rise by 7.4 percent over the past year.

Airbnb remains committed to working with Austin leaders to pioneer innovative solutions to support responsible tourism. We have long advocated for a level playing field for short-term rental platforms to collect and remit local tourism taxes on behalf of hosts in Austin and cities throughout Texas. In fact, Airbnb has tax agreements with Houston, Corpus Christi, Plano, and other cities across Texas to collect local hotel occupancy taxes (HOT) on all transactions made on our platform and remit them directly to the local jurisdiction. By allowing platforms to collect and remit local HOT on behalf of hosts in Austin, the City has the potential to both streamline the collection process and increase tax revenue, including for local arts initiatives, which receive nearly 10 percent of all local HOT in Austin.

View the full report here.